Artificial intelligence in the medical field: diagnostic capabilities of GPT-4 in comparison with physicians

Highlight box

Key findings

• Diagnostic accuracy: before providing laboratory/instrumental study results, GPT-4 achieved a 60% match with physicians for the first differential diagnosis and an 86% match within the top five differentials.

• Enhanced performance with data integration: incorporating laboratory and instrumental data increased GPT-4’s accuracy to 72% for the first differential and 92% within the top five.

What is known and what is new?

• Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4, has been increasingly explored for applications in medical diagnostics. For instance, a study on skin cancer detection demonstrated that AI using Convolutional Neural Networks could accurately diagnose melanoma cases and suggest comprehensive treatment strategies, often matching or exceeding dermatologist performance.

• This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of GPT-4’s diagnostic capabilities across multiple medical specialties in a real-world clinical context highlights variability in AI performance across different medical specialties, emphasizing the need for specialty-specific AI tools.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The study helped illustrate that advanced LLMs such as GPT-4, possess a great potential to become a useful tool, used to assist physicians or healthcare professionals in clinical settings. The frequency of correct diagnosis and the substantial improvement in diagnostic accuracy, when provided with comprehensive data integration, suggests that AI can effectively augment clinical decision-making when provided with complete patient information, as well as interpret complex laboratory and radiological findings.

• The findings of this study suggest that integrating AI tools like GPT-4 into clinical practice could offer significant benefits in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and efficiency. Healthcare institutions might explore the potential of incorporating such AI systems into their diagnostic workflows to support physicians in making more informed decisions.

Introduction

GPT-4 by open artificial intelligence (AI) is arguably one of the most advanced and widely used forms of large language model (LLM) systems, a subset of AI that focuses on processing and generating human language (1). These models are trained on extensive datasets, enabling them to predict and generate text sequences, allowing for human-like interactions. In addition to these abilities, the vast dataset of information held by these AI models create avenues for possible integration of these systems across various specialties.

Healthcare was one of the first areas where its usability was subjected to research, frequently assessed on its ability of multiple-choice test-taking (2-4). However, the idea of AI application in healthcare has been met with enthusiasm and skepticism (5,6). A key benefit of AI in healthcare could be its use to improve disease prevention, detection, diagnosis, and treatment by making repetitive tasks more time-efficient (7).

In this study, we attempted to explore how well the GPT-4 fares compared to human physicians. To note, we did not try to assess its ability to select next steps in management or handle cases independently, instead we evaluated GPT-4’s performance, when given the exact same information that the physician would use in their diagnostic process. It presented an opportunity to critically evaluate the potential of AI to augment and transform traditional diagnostic approaches. The implications of this research promise advancements in diagnostic accuracy and efficiency, ultimately enhancing patient care and outcomes in the medical field.

The evolution of AI has opened new possibilities in interpreting and utilizing vast amounts of medical data. For example, AI applications in neurology have shown promise in the early detection of cognitive disorders, as evidenced by the use of language processing models in identifying patterns indicative of early Alzheimer’s disease (8). Likewise, in another study detecting pneumonia from chest radiographs, deep learning algorithms have shown a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 64%, respectively, significantly improving compared to radiologists’ 50% and 73% (9). Additionally, a study on skin cancer detection revealed that, compared to dermatologists, an AI utilizing a Convolutional neural network could correctly diagnose melanoma cases and suggest comprehensive treatment strategies (10,11). Researchers have used AI technology for many additional disease states, including the detection of diabetic retinopathy (12), irregular electrocardiogram (ECG) readings, and the prediction of cardiovascular disease risk factors (13,14). However, these advancements have not been without controversy and gaps. A significant concern is the ability of AI to fully understand the nuances of patient history and symptoms, an area where human clinicians perform better (15). This emphasizes the need for further research.

In contrast to prior studies conducted with GPT-3 (16), such as the one that found GPT-3 capable of generating a differential diagnosis but significantly less accurate than the physicians (53.3% for GPT-3 vs. 93.3% for physicians). Our study utilizes GPT-4, a multimodal model which marks a considerable advancement in speed and accuracy in comparison to GPT-3 (17). By harnessing this newer iteration, our study also explores whether these advancements result in improved diagnostic performance.

Our study aimed to give additional insights into the role of AI in healthcare; the primary objective was to thoroughly assess GPT-4’s strengths and limitations in various medical fields by comparing its performance to that of experienced physicians. Additionally, we aimed to identify the difficulties AI faces in interpreting contextual patient information, laboratory and instrumental examination findings, and coming up with a relevant clinical diagnosis. This study intended to simulate a real-world clinical context to thoroughly analyze GPT-4’s performance by utilizing 340 patient cases that reflected diverse and realistic scenarios. The results indicated a notable alignment between GPT-4 and physicians’ diagnoses, with the inclusion of laboratory data significantly enhancing the AI’s accuracy. Besides this, we observed notable discrepancies in diagnostic accuracy between different specialties.

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tbilisi State Medical University (No. #4-2023/105) following its meeting on 21 July 2023, where it received a positive opinion and was approved without changes. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. The research is a retrospective observational study structured to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the AI language model GPT-4 compared with Physicians. These doctors were certified Georgian practitioners, affiliated with major hospitals across Tbilisi, Georgia, each made the diagnosis of a case within their respective specialties. The study used a dataset comprising 340 medical cases of patients ranging from 18 to 93 years of age (Figure 1), from different medical departments, including cardiology, gastroenterology, hematology, hepatology, infectious disease, nephrology, neurology, and pulmonology. Using such a diverse set of departments ensured a broad representation of clinical scenarios, in which we could compare if the diagnostic capabilities of the AI would match the physicians in terms of reaching a similar diagnosis.

The cases chosen for this study were rigorously checked and processed by us, a team of graduating medical students, to fit the following standards. The inclusion criteria of our study involved the following: patients who had a definitive diagnosis made by a physician and whose medical cases contained comprehensive information, including a complete history, physical examination data, instrumental studies, and relevant laboratory analysis. Medical cases were excluded, in case, if they contained no established diagnosis, had incomplete medical records, or the information provided was not sufficient to reliably accept the physician’s diagnosis.

The cases for this study were carefully handpicked by the research team to include a broad spectrum of medical conditions, ranging from relatively common diseases [e.g., myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), acute kidney injury (AKI), community-acquired pneumonia, gastroenteritis, urolithiasis, and transient ischemic attack] to rarer cases that physicians may encounter less frequently [e.g., cryptogenic cirrhosis, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, farmer’s lung (hypersensitivity pneumonitis), metastatic cancers like hepatocellular carcinoma or seminoma, hantavirus infection, and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis]. This approach was designed to reflect the full range of clinical conditions a practicing physician might encounter, represented proportionally to mirror the distribution of cases in typical clinical practice.

To ensure the validity of the diagnoses, we selected cases where diagnoses were confirmed either through highly specific diagnostic tests or by our close follow-up with these patients, where we observed their response to treatments or invasive procedures. We ensured, to the best of our knowledge, that each case represented an accurate and definitive diagnosis.

During the processing of cases, we meticulously removed any personal information and any data that could give GPT-4 an unfair advantage. This included details such as the reasoning behind the physician’s decision-making and specific confirmatory diagnostic tests that were typically ordered after the physicians had already developed a strong suspicion of the diagnosis. After processing, we differentiated the cases based on their chief complaints to simulate the initial presentation to a physician. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the study workflow, outlining the key steps from data collection through to statistical analysis and interpretation of results.

Each case was designed to include comprehensive data, with sufficient information for a physician to make a correct diagnosis with high accuracy. However, we excluded general tests like imaging studies or biopsies from providing a straightforward diagnosis. Instead, we provided the results exactly as reported by radiologists or pathologists, without any physician interpretation that would guide the AI directly to the diagnosis. For example, in a case involving Lyme disease, we removed the Lyme serology report. Similarly, for MI, we excluded interventional radiology reports that specified the exact location of vessel obstruction. We focused on including results that required clinical reasoning and evaluation rather than tests that would directly provide a final diagnosis.

All cases contained detailed patient history, thorough physical examination findings (including both positive and negative results), and the full set of laboratory and instrumental tests, minus those specifically excluded to prevent giving GPT-4 an undue advantage.

This study utilized GPT-4 as the AI model for several compelling reasons. Firstly, GPT-4 is arguably the most advanced LLM currently available, distinguished by its cutting-edge natural language processing capabilities. In addition, GPT-4’s extensive and diverse training data and 8,000 token capacity, allow it to process large amounts of information efficiently. Furthermore, with around 100 trillion parameters GPT-4 demonstrates exceptional complexity and precision in its responses (18).

The comparative analysis of diagnostic accuracy between the AI and the physician was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, the AI model was provided with only the patient’s history and physical examination findings. In the second phase, additional information was given to the AI, including the results of the patient’s laboratory analysis and instrumental studies. During each phase, the AI was instructed to give five most likely differential diagnoses ordered from most to least likely, based on the patient’s chief complaint and presenting symptoms, and by utilizing all the information it was given so far (Figure 3). Via this stepwise approach, we sought to replicate the real-world scenario of the sequential nature of clinical data accumulation in a physician’s everyday practice. To ensure consistency in the AI’s instructions and responses in all 340 cases, we employed a feature of GPT-4—“Custom Instructions” (19), in which we put the prompt outlined in Figure 4. This allowed the same instructions to be consistently applied across all new interactions automatically. There, we described to the AI the general purpose of our study and the basic methodology of our research, including the stepwise information provision method and the nuances mentioned above of its future responses. Using this feature, we could apply these exact custom instructions to every new chat and by proxy, every new medical case we provided, ensuring no inconsistencies in data provision between individual cases.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we employed various statistical methods to analyze the data by utilizing the Prism software. The primary assessment tool was logistic regression. Using it, we examined the likelihood of GPT-4’s and physicians’ diagnosis concordance across various specialties in both pre- and post-laboratory/instrumental findings implementation. Additionally, we used McNemar’s test to evaluate the level of significance that the implementation of laboratory data played in refining AI’s diagnostic accuracy. Finally, by utilizing the Chi-square analysis, we were able to stratify our findings based on medical departments and get a comparative view of the diagnostic outcomes both before and after laboratory and instrumental data was implemented (Tables 1,2). Via this statistical method, we examined how various data types influence the diagnosis in different medical specialties and the AI’s dependence on these data types to reach the correct diagnosis in the respective medical specialties.

Table 1

| Test | Chi-square statistic | P value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test 1: match in first differential | 26.35 | 0.001 | Significant association (P<0.05) |

| Test 2: match in first two differentials | 27.02 | 0.001 | Significant association (P<0.05) |

| Test 3: match in first three differentials | 25.37 | 0.002 | Significant association (P<0.05) |

| Test 4: match in first four differentials | 25.43 | 0.002 | Significant association (P<0.05) |

| Test 5: match in first five differentials | 20.26 | 0.01 | Significant association (P<0.05) |

Table 2

| Test | Chi-square statistic | P value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test 1: match in first differential | 15.89 | 0.06 | No significant association (P>0.05) |

| Test 2: match in first two differentials | 12.37 | 0.19 | No significant association (P>0.05) |

| Test 3: match in first three differentials | 11.75 | 0.22 | No significant association (P>0.05) |

| Test 4: match in first four differentials | 13.92 | 0.12 | No significant association (P>0.05) |

| Test 5: match in first five differentials | 14.55 | 0.10 | No significant association (P>0.05) |

Results

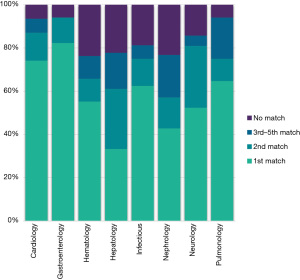

Comparing and analyzing the concordance between GPT-4 and physician diagnosis revealed many interesting findings. Even before laboratory and instrumental data inclusion, the matching rates demonstrated by the AI were 60%, 75%, and 86% for the first, first two, and all five differentials across various departments, respectively (Figures 5,6). However, adding laboratory and instrumental data increased the matching percentages to 72%, 85%, and 93% in the respective categories (Figures 6,7). Regarding department-specific performance, discrepancies in their matching percentages were seen before and after including the laboratory and instrumental data. The matching percentages were as low as 76% in nephrology in all five differentials in pre-laboratory/instrumental findings and as high as 99% matching in the 5 differentials post-laboratory/instrumental data implementation in pulmonology (Figure 8).

Logistic regression analysis further quantified the above-mentioned discrepancies. Picking as a reference the Department of Cardiology and comparing it to specialties like infectious disease and nephrology, the analysis showed approximately 67% less likelihood of reaching the correct diagnosis, indicated by a negative significant coefficient in these fields −1.1126 (P=0.01) and −1.1241 (P=0.01) in infectious disease and nephrology respectively.

An odds ratio test comparing the matching diagnosis before and after laboratory/instrumental data integration showed that in the latter case, the correct diagnosis rate was increased by a factor of 2.1 (P=0.008), effectively doubling the likelihood of accuracy.

McNemar’s test further corroborated these findings. It was conducted to measure the effect of laboratory data on AI’s diagnostic accuracy and, as a result, yielded a chi-squared value of 10.76, well above the threshold of the significance level of 3.841.

Finally, we also employed a chi-squared test, stratifying our results based on departments and measuring changes in diagnostic outcomes. Initially, when analyzing the pre-laboratory/instrumental data results, we observed a statistically significant difference across the different specialties, yielding a chi-square value of 26.35 and a P value of 0.001—in the first differentials, 27.02 and a P value of 0.001—in the first two differential and 20.26 and a P value of 0.01 in all 5 differentials (Table 1). Following the inclusion of laboratory/instrumental data, we repeated the analysis, resulting in a change in both values, the new chi-squared value being: 15.89 and a P value of 0.06—in the first differential, 12.37 and a P value of 0.19—in the first two differentials and 14.55 and a P value of 0.10 in all 5 differentials (Table 2). Indicating that the differences were no longer statistically significant.

Discussion

In an era where AI is increasingly implemented in medical practice (20), our study sought to critically assess the diagnostic accuracy of one of the most advanced LLM—GPT-4, compared to practicing physicians. By analyzing 340 clinical cases from various medical specialties, the study also aimed to understand the impact of comprehensive patient data, including medical history and laboratory findings, on the AI’s diagnostic performance.

Our findings align with recent research on GPT-4’s growing role in clinical practice. For instance, one study showed that GPT-4’s imaging approaches, based on patient history and clinical questions, matched the reference standard in 84 out of 100 cases. This suggests that GPT-4 could enhance clinical workflows and improve resource allocation (21). Another study found GPT-4 to be accurate in diagnosing myocarditis from CMR reports, highlighting its potential as a decision-support tool, particularly for less experienced physicians (22). Additionally, GPT-4 has been shown to simplify complex radiology reports into layperson-friendly language, helping to improve patient communication without losing accuracy (23).

In contrast to those findings, our study demonstrated a high degree of alignment between the GPT-4-generated differentials and physician-made diagnoses across various medical specialties. Several vital observations emerged from analyzing the percentages of matching diagnoses. Firstly, even without the implementation of laboratory and instrumental data, GPT-4’s diagnostic accuracy was notably high, achieving an impressive match rate of 60.7% in its first differential diagnosis; the concordance rates become more impressive looking at the top 5 differentials, indicating AI’s potential in clinical reasoning solely based on patient history and physical examination findings. Several studies have already underscored that AI excels in contextual data interpretation and can even surpass human performance in aspects such as radiologic image comprehension and patient data analysis (24).

Additionally, the results indicate that including laboratory information and instrumental examination findings significantly enhances the diagnostic accuracy of GPT-4. This suggests that while AI shows promising results in clinical diagnosis, its performance is markedly improved when it has access to a more complete patient chart. While expected, this aspect highlights the similarity in the diagnostic process of AI to that of a human physician. Parallel to this notion, a recent study published in the Lancet digital found that investigations using computer-aided diagnostics demonstrated excellent accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity in detecting small radiographic abnormalities (25). However, unlike in the aforementioned studies where AI systems directly analyzed radiographic images, in our research, all the images provided to GPT-4 were followed up by descriptions of radiological findings, interpreted and documented by certified radiologists. These descriptions contained detailed observations without revealing the final diagnosis. This approach mirrors the clinical reality where physicians often rely on radiologists’ reports rather than the raw images.

A recent systematic review of over 40 research papers further shows that AI use in laboratory medicine can help physicians with clinical decision-making, monitor diseases, and improve patient safety outcomes (26). As seen in multiple studies across different medical specialties, the prospect of AI integration is as relevant as ever, with fields such as radiology, cardiology, and internal medicine/general practice with the most US Food & Drugs Administration (FDA)-approved AI technologies on the market—30, 16, and 10 respectively (27). Promising results have also been seen with deep learning machines for detecting breast (28) and lung cancer (29).

The discrepancies between the matching rates of different departments, which were additionally confounded by the integration of laboratory and instrumental data, further raise many interesting points. Departments like nephrology and hematology, compared to others, showed a relatively low matching rate before the laboratory and instrumental data were provided (Figures 9,10), yet after doing so, their rates showed a significant increase; on the other hand, in departments such as pulmonology and neurology, additional data had a relatively little effect (Figures 9,10). These findings can be explained by examining the nuanced effects of different data and information on influencing the diagnostic process in different departments. Additional findings such as blood work and imaging results have tremendous value across all specialties. For example, fields such as nephrology and hematology depend heavily on laboratory results, urinalysis, or complete blood counts to reach the correct diagnosis. On the other hand, in the departments of pulmonology and neurology, diagnosing a medical condition is more clinical, relying on history and physical examination findings while using the results from analyses or instrumental findings primarily as a confirmatory tool rather than a purely diagnostic one. Considering this, we can assume that the AI system operates via the same principles and that different types of data hold varying degrees of weight in their ability to influence the likelihood of generating the correct diagnosis respective to their field of medicine. The peculiarities of this discussion can be explored further in greater detail by isolating and dividing the information provided to the AI into specific subtypes and analyzing their impact on GPT-4’s diagnostic performance separately.

Our study employed the chi-squared test to evaluate the diagnostic performance of GPT-4 compared to physicians, with a focus on differences across medical specialties. This analysis was conducted both before and after the inclusion of laboratory and instrumental data. Initially, our findings revealed a statistically significant variance in diagnostic outcomes among different specialties—indicating that some specialties are more heavily dependent on data like—clinical history and physical examination findings, compared to others. Upon incorporating laboratory and instrumental data, a significant shift was found—the previously observed differences across specialties were no longer statistically significant. This indicated that as long as the AI is given comprehensive and field specific information, GPT-4’s accuracy across different medical specialties is the same.

To further corroborate the topic of discrepancies across various medical specialties, also notable is the information that our study highlighted that cardiology, respiratory medicine, and hematology demonstrated higher accuracy rates. This is contrasted by lower rates in infectious diseases and nephrology, attributed to the inherently complex nature of diseases in these fields. Infectious diseases often manifest with non-specific symptoms like fever, which can stem from various pathogens, making accurate diagnosis challenging. In contrast, Cardiology typically presents more distinct, recognizable patterns, aiding in more accurate AI-driven diagnoses, such as those by GPT-4. The precision in Cardiology is also likely enhanced by using quantifiable diagnostic tools like ECGs, providing clearer data for AI analysis. Building on this, AI’s capabilities extend to the interpretation of echocardiograms, where it can accurately detect features such as pacemaker leads, an enlarged left atrium, left ventricular hypertrophy, and assess crucial measurements like left ventricular end-systolic and diastolic volumes, and ejection fraction (30).

Those findings mirror results from a meta-analysis evaluating deep learning models (31). Deep learning models are trained using a large set of data and neural network architectures that learn features from the provided data without requiring manual feature extraction in ophthalmology, respiratory imaging, and breast imaging, with ophthalmology achieving the highest accuracy. This underscores the importance of quality, diverse datasets, and standardized reporting for advancing deep learning in medical diagnostics (32).

As concluded from previous papers, the excitement and anticipation surrounding AI have surpassed the scientific progress made in the field, particularly in terms of its validation and preparedness for use in patient care (33). It is essential to acknowledge and address the limitations and issues associated with using AI in medicine and clinical decision-making, as this ensures the responsible and ethical implementation of these technologies (34). Data privacy and security measures are paramount to protect against data breaches and misuse (35). Additionally, various other shortcomings limit its effectiveness for research, including a propensity to offer incorrect answers and to repeat phrases from earlier conversations, which can lead to many medical errors (34). Recently, there’s been a growing fascination with AI-driven chatbot symptom checker applications. These platforms use AI techniques to simulate human-like interactions, providing users with possible diagnoses and helping them with self-triage (26). Using AI for self-diagnosis without consulting a doctor can be risky and potentially harmful, as AI can sometimes produce biased and incorrect results (36).

Another notable and concerning issue is that of data breaches and hacking of AI technologies, and the more widespread use of Artificial technologies could exacerbate this issue (34). From late 2009, when the HHS OCR began sharing summaries of healthcare data breaches, through the end of 2023, there were 5,887 significant breaches reported in this sector. This trend saw a notable rise during the 2020s (36). Additionally, there’s a concern about the intentional manipulation of algorithms to cause widespread harm, such as causing excessive insulin delivery in diabetic patients or triggering unnecessary defibrillator activations in heart disease patients. Additionally, the growing ability to identify individuals through facial recognition or genetic sequencing from large databases poses significant challenges to privacy protection (37,38).

Our study has important implications for the future integration of AI in medical diagnosis. It emphasizes the need for AI systems to access complete patient data, including clinical findings and laboratory results, to maximize their diagnostic potential. This also highlights the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in AI development, ensuring the system is well-informed by the nuances of different medical specialties.

Despite the extensive approach of our study in assessing GPT-4’s diagnostic accuracy in medical scenarios, several limitations and methodological considerations must be highlighted. The study’s design as a retrospective observational study limits the dynamic interactivity inherent in actual clinical environments. In real-world settings, patient presentations and clinical data are not static but evolve, which could influence the AI’s performance in ways not captured in our controlled study setting. This aspect raises questions about the direct applicability and transferability of our findings to live clinical contexts.

Furthermore, while diverse and substantial, the study’s reliance on a preselected dataset of medical cases may not fully represent the vast complexity encountered in clinical practice. Notably, the dataset may underrepresent rare or unusual cases, which are often the most challenging in terms of diagnosis. This limitation could affect the AI’s demonstrated diagnostic capabilities and suggests a need for caution when generalizing the results to broader clinical scenarios.

While the study provides valuable insights, it also opens up avenues for future research—for example, longitudinal studies to monitor the performance of AI in real-time clinical settings over extended periods. Additionally, given the variations in diagnostic accuracy across different medical specialties, there’s potential for developing specialized AI models tailored to each medical field’s unique diagnostic needs and data types by analyzing how AI interprets and weighs different types of data across various medical conditions. Research could focus on creating these models and further refining AI algorithms.

GPT-4’s diagnostic abilities suggest it could soon become an integral part of medical practice. For example, it could act as a decision-support tool for physicians by offering real-time differential diagnoses. This assistance can enhance clinical reasoning and help reduce diagnostic errors. By presenting evidence-based suggestions, GPT-4 encourages doctors to consider a wider range of possible conditions, which is particularly useful in complex or unclear cases. This approach not only aims to improve diagnostic accuracy but also to enhance patient outcomes.

In addition, GPT-4 holds promise for medical education and training. It can provide students and residents with an interactive platform to practice and sharpen their diagnostic skills using simulated case studies.

Conclusions

This study rigorously evaluated GPT-4’s diagnostic performance against that of experienced physicians across eight medical specialties using 340 clinical cases. GPT-4 demonstrated a commendable diagnostic accuracy, matching physicians’ primary diagnoses in 60% of cases and achieving an 86% concordance within the top five differentials. Notably, the incorporation of laboratory and instrumental data elevated GPT-4’s accuracy to 72% for the primary diagnosis and 92% within the top five, underscoring the critical role of comprehensive data integration in enhancing AI diagnostic capabilities.

Performance variability across specialties was evident, with significant improvements observed in Nephrology from 76% to 99% concordance post-data integration, while Pulmonology maintained consistently high accuracy. This disparity highlights the necessity for specialty-specific AI models tailored to the unique diagnostic demands and data dependencies of each medical field. Such customization could optimize AI support, ensuring relevance and effectiveness in diverse clinical contexts.

Despite these promising results, the study’s retrospective design and the potential underrepresentation of rare or complex cases limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, ethical considerations surrounding data privacy and the imperative for ongoing validation of AI models remain paramount to the responsible deployment of AI in healthcare settings.

Future research should focus on prospective, real-time clinical evaluations to better capture the dynamic nature of patient care and further validate AI’s diagnostic utility. Additionally, developing specialized AI models for distinct medical disciplines and ensuring continuous algorithmic refinement will be essential to fully harness AI’s potential in augmenting clinical decision-making. By addressing these areas, the integration of AI technologies like GPT-4 can significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy, streamline clinical workflows, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jmai.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jmai-24-276/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jmai.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jmai-24-276/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jmai.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jmai-24-276/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tbilisi State Medical University (No. #4-2023/105) following its meeting on 21 July 2023, where it received a positive opinion and was approved without changes. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Liu Y, Han T, Ma S, et al. Summary of ChatGPT-Related research and perspective towards the future of large language models. Meta-Radiol 2023;1:100017. [Crossref]

- Capabilities of GPT-4 on Medical Challenge Problems. ar5iv. [cited 2024 Jan 25]. Available online: https://ar5iv.labs.arxiv.org/html/2303.13375

- Brin D, Sorin V, Vaid A, et al. Comparing ChatGPT and GPT-4 performance in USMLE soft skill assessments. Sci Rep 2023;13:16492. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu L, Mou W, Yang T, et al. ChatGPT can pass the AHA exams: Open-ended questions outperform multiple-choice format. Resuscitation 2023;188:109783. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan B, Fatima H, Qureshi A, et al. Drawbacks of Artificial Intelligence and Their Potential Solutions in the Healthcare Sector. Biomed Mater Devices 2023; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alowais SA, Alghamdi SS, Alsuhebany N, et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med Educ 2023;23:689. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fogel AL, Kvedar JC. Artificial intelligence powers digital medicine. NPJ Digit Med 2018;1:5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agbavor F, Liang H. Predicting dementia from spontaneous speech using large language models. PLOS Digital Health 2022;1:e0000168. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Becker J, Decker JA, Römmele C, et al. Artificial Intelligence-Based Detection of Pneumonia in Chest Radiographs. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12:1465. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han SS, Park I, Eun Chang S, et al. Augmented Intelligence Dermatology: Deep Neural Networks Empower Medical Professionals in Diagnosing Skin Cancer and Predicting Treatment Options for 134 Skin Disorders. J Invest Dermatol 2020;140:1753-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haenssle HA, Fink C, Schneiderbauer R, et al. Man against machine: diagnostic performance of a deep learning convolutional neural network for dermoscopic melanoma recognition in comparison to 58 dermatologists. Ann Oncol 2018;29:1836-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li S, Zhao R, Zou H. Artificial intelligence for diabetic retinopathy. Chin Med J (Engl) 2021;135:253-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alfaras M, Soriano MC, Ortín S. A Fast Machine Learning Model for ECG-Based Heartbeat Classification and Arrhythmia Detection. Front Phys 2019;7:103. [Crossref]

- Raghunath S, Pfeifer JM, Ulloa-Cerna AE, et al. Deep Neural Networks Can Predict New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation From the 12-Lead ECG and Help Identify Those at Risk of Atrial Fibrillation-Related Stroke. Circulation 2021;143:1287-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gordon W. Moving Past the Promise of AI to Real Uses in Health Care Delivery. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv 2022;3: [Crossref]

- Hirosawa T, Harada Y, Yokose M, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Differential-Diagnosis Lists Generated by Generative Pretrained Transformer 3 Chatbot for Clinical Vignettes with Common Chief Complaints: A Pilot Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:3378. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- GPT-4 vs. GPT-3. OpenAI Models’ Comparison | Neoteric. Neoteric Custom Software Development Company. 2023. Available online: https://neoteric.eu/blog/gpt-4-vs-gpt-3-openai-models-comparison/

- OpenAI Platform. [cited 2024 Jan 25]. Available online: https://platform.openai.com

- Custom instructions for ChatGPT. Openai.com. 2023. Available online: https://openai.com/index/custom-instructions-for-chatgpt/

- Krishnan G, Singh S, Pathania M, et al. Artificial intelligence in clinical medicine: catalyzing a sustainable global healthcare paradigm. Front Artif Intell 2023;6: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gertz RJ, Bunck AC, Lennartz S, et al. GPT-4 for Automated Determination of Radiological Study and Protocol based on Radiology Request Forms: A Feasibility Study. Radiology 2023;307:e230877. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaya K, Gietzen C, Hahnfeldt R, et al. Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 analysis of cardiovascular magnetic resonance reports in suspected myocarditis: A multicenter study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2024;26:101068. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salam B, Kravchenko D, Nowak S, et al. Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 makes cardiovascular magnetic resonance reports easy to understand. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2024;26:101035. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KH, Lee RW, Kwon YE. Validation of a Deep Learning Chest X-ray Interpretation Model: Integrating Large-Scale AI and Large Language Models for Comparative Analysis with ChatGPT. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023;14:90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. Artificial intelligence in medical imaging: switching from radiographic pathological data to clinically meaningful endpoints. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2:e486-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Undru TR, Uday U, Lakshmi JT, et al. Integrating Artificial Intelligence for Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis - a Review. Maedica (Bucur) 2022;17:420-6. [PubMed]

- Benjamens S, Dhunnoo P, Meskó B. The state of artificial intelligence-based FDA-approved medical devices and algorithms: an online database. NPJ Digit Med 2020;3:118. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhowmik A, Eskreis-Winkler S. Deep learning in breast imaging. BJR Open 2022;4:20210060. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cellina M, Cacioppa LM, Cè M, et al. Artificial Intelligence in Lung Cancer Screening: The Future Is Now. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:4344. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani A, Ouyang D, Abid A, et al. Deep learning interpretation of echocardiograms. NPJ Digit Med 2020;3:10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Deep Learning. MIT Press. [cited 2024 Jan 25]. Available online: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262035613/deep-learning/

- Aggarwal R, Sounderajah V, Martin G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of deep learning in medical imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit Med 2021;4:65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine 2019;25:44-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dave T, Athaluri SA, Singh S. ChatGPT in medicine: an overview of its applications, advantages, limitations, future prospects, and ethical considerations. Front Artif Intell 2023;6:1169595. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI | Shaping Europe’s digital future. 2019 [cited 2024 Jan 25]. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai

- You Y, Gui X. Self-Diagnosis through AI-enabled Chatbot-based Symptom Checkers: User Experiences and Design Considerations. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2020;2020:1354-63. [PubMed]

- Finlayson SG, Chung HW, Kohane IS, et al. Adversarial Attacks Against Medical Deep Learning Systems. 2019 [cited 2024 Jan 25]. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1804.05296

- Brundage M, Avin S, Clark J, et al. The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation. 2018 [cited 2024 Jan 25]. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.07228

Cite this article as: Gvajaia N, Kutchava L, Alavidze L, Yandamuri SP, Pestvenidze E, Kupradze V. Artificial intelligence in the medical field: diagnostic capabilities of GPT-4 in comparison with physicians. J Med Artif Intell 2025;8:20.